Prince Siddhartha Gautama in the Christian calendar

- Daniel Oltean

- Jun 28, 2025

- 5 min read

Updated: Jul 6, 2025

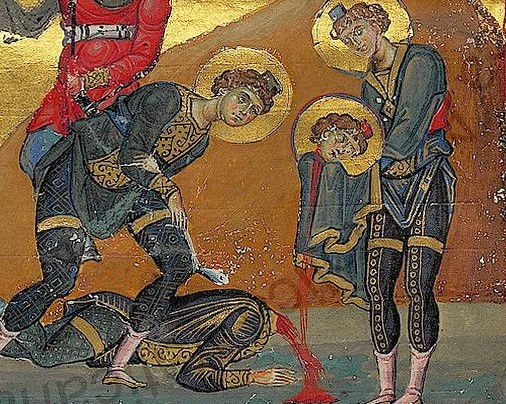

Tales, like proverbs, have always traveled, knowing no borders. It is the case of an ancient Indian legend that, transformed into an edifying tale and then a hagiographic text, enjoyed great success in the Middle Ages. From the 11th century, its hero, the Hindu prince Siddhartha Gautama, entered the Georgian (May 19), Greek (August 26), Latin (November 27), Slavic, and Romanian (November 19) calendars, under the name of Josaphat.

A legend of Oriental origin and its transmission to Byzantium

According to legend, Siddhartha Gautama was born as the son of the king of Kapilavastu, in northern India. Raised in luxury and surrounded by pleasures, the prince apparently did not know the sadness of the world until he successively encountered an older man, a cripple, and a dead man. Having become aware of the vicissitudes of the human condition, Siddhartha abandoned his wife and child to lead a life of wandering following a fourth encounter, this time with an ascetic. Having attained the perfect knowledge of all things and surrounded by many disciples attracted by his teachings, the prince is said to have ended his life at the age of eighty. The legend, known in its broad outlines by the 2nd century BC at the latest, is preserved in sacred texts in several Indian languages (Pali, Sanskrit, Prakrit) from the 2nd to 4th centuries AD. [1]

Later, the text was enriched with numerous parables and wisdom stories from different cultures. First, either directly or through the languages of Central Asia, the tale was translated into Pahlavi (Middle Persian). In turn, the new version served as a source for Arabic translations, starting in the 8th century. The Arabic text was adapted to the local religious context. The spiritual path of the prince, now known as Budhasaf, became a conversion from idolatry to an ascetic religion not well-defined, but monotheistic. The ascetic briefly encountered by Prince Siddhartha is transformed into a key figure, named Bilawhar, who guides the prince to perfection. [2]

One of the Arabic versions led to the translation of the text into Georgian in the 9th century, probably in Palestine. Compared to the Arabic version, the Georgian text adds or modifies several elements: the prince’s father becomes a pagan king who persecutes Christians; the monk who gains the prince’s trust teaches him the Christian faith; like the prince, his father also converted to Christianity; upon the latter’s death, the prince leaves the kingdom to his friend Barachiah and joins the monk in the desert, where both end their lives in holiness. [3]

Finally, the Georgian text was translated into Greek in the late 10th or early 11th century by Euthymios the Athonite, the abbot of the Iviron Monastery. The translator altered the narrative by adding numerous biblical and patristic quotations, as well as an apologetic text written by the philosopher Aristides of Athens (2nd century). [4] The Greek text served as the source for the first Latin translation, made in Constantinople in the mid-11th century. [5]

Prince Siddhartha Gautama, better known as Buddha, meaning “the awakened one,” as his disciples called him, thus entered Christian worship. In the original story, the hero is referred to, in Sanskrit and Pali, as Bodhisattva, which means “one who desires/is in the process of achieving enlightenment.” This name later became Budhasf/Budhasaf/Yudasaf in Arabic, Iodasaph in Georgian, Ioasaph in Greek, and Josaphat in Latin. A similar transformation led to the name Barlaam, the spiritual master who is said to have guided Josaphat. [6]

The relics of Prince Siddhartha/Buddha/Saint Josaphat in Antwerp

According to the Georgian, Greek, and Latin versions of the novel, after Josaphat’s death, King Barachiah went into the desert and found his body incorrupt. He took the relics with all the honors and placed them in a golden shrine, with those of Barlaam. The faithful came in large numbers to venerate the relics, and miracles soon began to occur. A church was then built over the tombs of the two saints. [7]

These indications, apparently accurate, have inspired the false idea that the tale is real, Saint Josaphat protects us from above, and his relics truly exist. Some have even found them! Thus, in 1672, the remains of Josaphat are attested in a group of 36 relics belonging to the Cistercian monastery of Saint-Saviour in Antwerp, led at that time by Abbot François Diericx (1668-1688). According to documents of dubious authenticity, most of the relics belonged to the kings of Portugal and were offered in 1633 to Abbot Christophe Butkens (1631-1650). The gift is said to have been mediated by Dionysius, a monk at Saint-Saviour and son of King Anthony, the last Portuguese sovereign before the Spanish conquest of 1580. In this group of relics, those of Josaphat are said to have been offered by Doge Alvise I Mocenigo (1570-1571) of Venice to King Sebastian I of Portugal (1557-1578) in 1571. [8] After the closure of the Abbey of Saint-Saviour, the reliquary was transferred to the Church of Saint Andrew in Antwerp, where it is preserved and venerated to this day.

[1] Aśvahghoṣa, The Buddhacarita, ed. and trans. E. H. Johnston, Delhi, 1972.

[2] Le Livre de Bilawhar et Būḏāsf selon la version arabe ismaélienne, ed. D. Gimaret, Geneva, 1971.

[3] D. M. Lang, The Balavariani (Barlaam and Josaphat): A Tale from the Christian East Translated from the Old Georgian, Los Angeles, 1966 (extended version); D. M. Lang, The Wisdom of Balahvar (A Christian Legend of the Buddha), London, 1957; A. Mahé – J.-P. Mahé, La sagesse de Balahvar. Une vie christianisée du Bouddha, Paris, 1993, p. 144 (short version).

[4] R. Volk, Die Schriften des Johannes von Damaskos, VI/2: Historia animae utilis de Barlaam et Ioasaph (spuria) (Patristische Texte und Studien, 60), Berlin, 2006, trans. G. R. Woodward – H. Mattingly, John Damascene, Barlaam and Ioasaph (Loeb Classical Library, 34), Cambridge (MA), 1967 (1914). See also R. Volk, From the Desert to the Holy Mountain: The Beneficial Story of Barlaam and Ioasaph, in C. Cupane – B. Krönung (ed.), Fictional Storytelling in the Medieval Eastern Mediterranean and Beyond (Brill’s Companions to the Byzantine World, 1), Leiden, 2016, p. 401-426.

[5] J. Martínez Gázquez, Hystoria Barlae et Iosaphat (Bibl. Nacional de Nápoles VIII.B.10) (Nueva Roma, 5), Madrid, 1997.

[6] A similar fate befell the book of fables known as Kalila and Dimna or The Fables of Bidpai. The fables, originating from texts of Indian origin (Panchatantra, Mahabharata, etc.), were translated from one language to another almost along the same route and at the same time intervals: into Pahlavi in the 6th century, into Arabic in the 8th century, and finally into Greek in the 11th century (this time under the name Stephanites and Ichnelates). As for the Book of Sinbad/Syntipas the Philosopher (known in the West as The Romance of the Seven Sages), of Indian or Persian origin, it was translated into Greek in the 11th century from a Syriac text, which most likely came from an Arabic source.

[7] Georgian extended version, §68, trans. Lang, p. 180, https://archive.org/details/LangBalavariani/page/n173/mode/1up; Georgian short version, trans. Lang, p. 122, trans. Mahé – Mahé, p. 144; Greek version, §40, ed. Volk, p. 402-404, trans. Woodward – Mattingly, p. 607-609, https://archive.org/details/in.ernet.dli.2015.232211/page/607/mode/1up.

[8] Acta Sanctorum Apr., I, 74D; 889E, Paris, 1866; Oct., IV, 260C, Paris, 1866.