Losing your head and finding it again

- Daniel Oltean

- Jun 29, 2025

- 6 min read

Updated: Nov 16, 2025

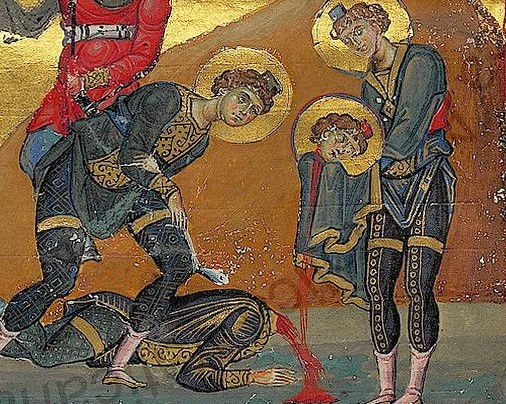

In ancient times, losing one’s head was not an exceptional occurrence. Wars, conflicts of all kinds, and punishments could easily result in death by decapitation. Among those condemned to this type of death, hagiographic texts present the cases of several Christian martyrs. Some of them are said to have benefited from a particular miracle: after their separation, the head and body reunited so perfectly that there was no evidence to suggest that a violent death had occurred.

Heads and bodies miraculously reunited

A notable example is the case of the martyr George. According to the oldest text describing his sufferings, written in the 4th or 5th century (BHG 670a), the saint would have been killed three times by the infidels and then resurrected three times by Christ, before his final death. When George died for the first time, his body would have been cut into ten pieces and thrown into a pit, but Archangel Michael intervened and rebuilt it. Then, Christ restored him to life, just as he had given to Adam. [1] The legend is preserved in later Coptic tradition, which considers that several martyrs, such as Pahnutius, Lacaron, Anoub, and Philotheus, would have suffered a similar fate. Cut into pieces, they were healed by divine intervention and brought back to life. [2]

The topic is also present, in another form, in the Martyrdom of the Prophet Daniel and the Three Children Ananias, Azarias, and Misael. The text, probably of Egyptian origin or influence, is attributed to either Athanasius of Alexandria (BHG 484z-484*) or Cyril of Alexandria (BHG 487-487a). According to this account, summarized in the Byzantine synaxarion, Daniel and his companions would have been decapitated, but then each head was miraculously reattached to its body. [3] This time, a resurrection did not take place.

The miracle of the reunification of the head and body after the beheading is found in several geographical areas and at different times. In the Pontus region (Turkey), the Life of Bishop Basil of Amasea (4th c., April 26, BHG 239) tells how the head and body of the saint were perfectly reunited in the sea, where they had been thrown. [4] An identical story is included in the Life of Fabius of Caesarea (Mauretania, 4th c., BHL 2818). [5] According to the legend of Chrysogonus of Aquileia (province of Udine, Italy, 4th c., BHL 1795), it was a priest named Zoilus who found the remains of the martyr and miraculously reunited them. [6] As for Bishop Herculanus of Perugia (6th c.), when the faithful exhumed his relics forty days after his beheading, they discovered the head perfectly welded to the body. According to the testimony of Pope Gregory I,

his head was united to the body as if it had never been severed, and indeed there was no apparent trace of severance. [7]

According to a story preserved in several ancient languages, the head of Paul the Apostle would have been discovered by a shepherd, placed near the feet of Paul’s remains, and then miraculously reunited with the rest of the body. The legend is included in the Georgian and Latin versions of the Letter of Pseudo-Dionysius the Areopagite to Timothy (CANT 197, BHL 6671), translations of a lost Greek source, [8] as well as in several Syriac texts. [9] A somewhat different variant is found in the Middle Irish version of Pseudo-Marcellus’s Acts of Peter and Paul; it is said that Paul’s head remained in a lake near the site of the beheading for forty years before being discovered. [10]

A universal myth

For medieval man, the success of this legendary tale is easily explained by its attractive and reassuring message: the beheading of saints did not prevent the later reunification of the head with the body and, eventually, their joint resurrection. Moreover, the legend offered the faithful the opportunity to venerate the body in its entirety and, to a certain extent, prevented the fragmentation of relics.

The legend is not limited to the Christian sphere. According to the Pyramid Texts (ca. 24th-20th c. BC), the Egyptian god Osiris was killed and cut into pieces by his brother Seth, but later was found, recomposed, and resurrected by his sister and wife Isis. [11] In the Greek pantheon, the god Dionysos suffered the same fate: torn to pieces by the Titans, his remains were first gathered up either by his mother Demeter or by his brother Apollo, and then brought back to life. [12] According to Hindu myths preserved in the Mahabharata (ca. 3rd c. BC-3rd CE), after her beheading, Renouka, the mother of Parashurama (the sixth avatar of the god Vishnu), was brought back to life. Later legends transformed Renouka into a goddess whose body was accidentally united not with her head, but with that of another person, [13] a tradition that probably inspired Marguerite Yourcenar in her tale Kali beheaded. [14] In fact, the legend particularises a universal myth that affirms the superiority of life over death. The Christian tradition, which took up and developed this legend, also included it in the Lives of the cephalophore saints (who are said to have carried their heads in their hands after decapitation).

[1] K. Krumbacher, Der heilige Georg in der griechischen Überlieferung (Abhandlungen der königlich bayerischen Akademie der Wissenschaften, Philosophisch-philologische und historiche Klasse, 25.3), Munich, 1911, p. 3‑16, at 6. See also Nikolaos Kälviäinen, The Greek Martyrdom of George, The Cult of Saints in Late Antiquity, http://csla.history.ox.ac.uk/record.php?recid=E06147; E. A. Wallis Budge, The Martyrdom and Miracles of Saint George of Cappadocia, London, 1888, p. 203‑235, at 212‑213 (English translation of the Coptic version). BHG refers to Bibliotheca Hgiographica Graeca.

[2] J.-M. Sauget, Paphnuzio di Denderah, in Bibliotheca Sanctorum, 10, Rome, 1968, col. 29-35; T. Orlandi, Lacaron, saint, in The Coptic Encyclopedia, 5, New York, 1991, p. 1423‑1424; Idem, Anub, saint, in The Coptic Encyclopedia, 1, p. 152; A. Rogozhina, “And from his side came blood and milk”: The Martyrdom of St Philotheus of Antioch in Coptic Egypt and Beyond (Gorgias Eastern Christian Studies, 52), Piscataway (NJ), 2019, p. 355‑356.

[3] H. Delehaye, Synaxarium Ecclesiae Constantinopolitanae, Acta Sanctorum Propylaeum Novembris, Brussels, 1902, col. 319.23‑24.

[4] Acta Sanctorum April, III, p. xlii‑xlvi, at xlv, Paris, 1866 (§19).

[5] G. Eldarov, Fabio il Vessillifero, in Bibliotheca Sanctorum, 5, Rome, 1964, col. 430. BHL refers to Bibliotheca Hagiographica Latina.

[6] P. F. Moretti, La Passio Anastasiae. Introduzione, testo critico, traduzione, Rome, 2006, p. 120‑123, English trans. M. Lapidge, The Roman Martyrs (Oxford Early Christian Studies), Oxford, 2018, p. 69‑70 (§9); M. Pignot, The Latin Martyrdom of Anastasia and Companions, The Cult of Saints in Late Antiquity, http://csla.history.ox.ac.uk/record.php?recid=E02482.

[7] A. de Vogüé (ed.) - P. Antin (trans.), Grégoire Ier, Dialogues, §3.13 (Sources chrétiennes, 260), Paris, 1979, p. 302‑303. See E. Bozoky, Têtes coupées des saints au Moyen Âge. Martyrs, miracles, reliques, dans Babel. Littératures plurielle, 42 (2020), p. 133‑168, https://journals.openedition.org/babel/11516?lang=fr.

[8] C. Macé, La lettre de Denys l’Aréopagite à Timothée sur la mort des apôtres Pierre et Paul. L’apport de la version géorgienne, in Apocrypha, 31 (2020), p. 61‑104, at 94‑97; D. L. Eastman, Epistle of Pseudo-Dionysius the Areopagite to Timothy, e-Clavis: Christian Apocrypha, https://www.nasscal.com/e-clavis-christian-apocrypha/epistle-of-pseudo-dionysius-the-areopagite-to-timothy. CANT refers to Clavis Apocryphorum Novi Testamenti.

[9] J. A. Doole, The miracle of the Apostle’s re-attaching head, in Apocrypha, 30 (2019), p. 87‑106, at 94‑101.

[10] R. Atkinson, The Passions and the Homilies from Leabhar Breac, Dublin 1887, p. 86‑95, at 93, trans. 329‑339, at 337.

[11] J. P. Allen, The Ancient Egyptian Pyramid Texts, §364, 616a, Atlanta (GE), 2005, p. 80; §606, 1684a-c, trans. p. 226; §670, 1981b-c, trans. p. 267. Cf. B. Mathieu, Mais qui est donc Osiris ? Ou la politique sous le linceul de la religion, in Égypte Nilotique et Méditerranéenne, 3 (2010), p. 77‑107, at 103. See also Plutarque, Œuvres morales, §23, Isis et Osiris, ed. and trans. C. Froidefond, Paris, 1988.

[12] Diodorus of Sicily, The Library of History, §3.62.6, trans. C. H. Oldfather, vol. 2, p. 286-287, https://archive.org/details/in.ernet.dli.2015.279944/page/n295/mode/2up; Lycophronis, Alexandra, vol. 2, Scholia, §207, ed. E. Scheer, Berlin, 1908, p. 97.

[13] J. Assayag, La colère de la déesse décapitée. Traditions, cultes et pouvoir dans le sud de l’Inde, Paris, 1992; A. Jaganathan, Yellamma Cult and Divine Prostitution: Its Historical and Cultural Background, in International Journal of Scientific and Research Publications, 3.4 (2013), https://www.ijsrp.org/research-paper-0413/ijsrp-p1681.pdf.

[14] M. Yourcenar, Kali décapitée, in Nouvelles orientales, Paris, 1938, http://www.cidmy.be/images/stories/pdf/kali_decapitee.pdf (first version, 1928), https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=PNCqRJ1Y-2s (audio).